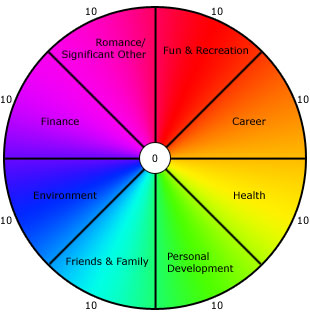

Beginning of Life indicates the Wheel of Life

Posted in Comparative studies, Contemporary Buddhism, History, honesty life, How to Meditate, inter-change, Knowledge and wisdom, life and way, Mutual Understanding

By Sona Kanti Barua

|

| Wheel of Life |

The

wheel of life as portrayed in Tibetan art and Japanese art in the circle, the

hog represents ignorance (Moha), the cock represents desire (raga) and snake

represents aversion (dosa). Despite this recent progress, I think it

exaggeration to say that Buddha’s Dependent Origination (Paticca Samuppada)

theory of cause and effect and the Middle

Way are still applicant to moral development of mankind

and the very best universal theory. It

seems the comparison of the wheel of life with scientific outlook. Buddhism

teaches that all compounded things come into being, presently exist and ceases

dependent on conditions and causes.

Newsweek of May 7, 2001 published a

cover story on “Science & the Spirit”. In this essay there are comments on

Buddhism, ”Scientists are using brain imaging to pinpoint the circuits that are

active when Tibetan Buddhists mediate.”…10

According

to Buddhism ignorance is the ultimate beginning of life.

This question so

frequently put is ignorance manifest. To speak of a beginning where there is no

entity is a sheer impossibility. A process can have to no beginning but as it

is beginning constantly, have no end, but is ceasing constantly. Not to

understand this is ignorance, and dependent on ignorance and raised

karma-formations, which through processes of conscious grasping lead to rebirth

in which is suffering.

Time

and space are subject to change in Buddhism.

|

| Time and Space according to Buddhist Rebirth perspective |

It

is also remarkable that Radmila Moacanin explained concerning self and etc. in

his book entitled “Jungian Psychology and Buddhism.” 11The

approaches of Jung and the teachings of Buddhism have often been looked at

together. The writer (R. Moacanin) examines archetypes, collective unconscious,

the self, Jung’s famous mandala

experiences and the teachings of Buddha’s Eightfold (Middle ) Path and Tantric

Buddhism.

Buddhism asked what is self?

|

Dr. Leonard C.D.C.

Priestley professor, edited and wrote a book entitled “The Reality of the

Indeterminate Self or Pudgalava Buddhism.” He explained in the page 54,”The

pudgala, then, is a self which is indeterminate in the sense that it is neither

the same as the dharmas by which it is identified nor separated from

them.” 12

The Heart of Buddhist Wisdom: Human life is made of 5 aggregates.

|

| 5 Aggregates in Buddhism |

We live in the period

of which is dominated by the amazing achievement in the field of science and

technology. Every aspect of our daily life is permeated by science and what is

today called the Scientific Method it was used over 2600 years ago by

Lord Buddha. Human life is made of five aggregates. The Buddha explained five

aggregates (1) Form or body is like a foam (2) feeling is like a water

–bubble (3) Perception or discriminate

mentality is like a mirage (4) conditionings are like a banana tree and (5)

Consciousness like a magic or illusion. There are several discourses of the

Buddha on the five aggregates of attachment.16

What the Buddha

taught is: (1) all things (life, time and space) are impermanent or in a flux

(2) what is changing, it creates sufferings or feelings of discontent and (3)

non – entity (Anatta): The teaching of Buddha does not proclaim that there is

no individuality, no –self, but only that there is no permanent individuality,

no unchanging self. So this individuality has no permanent existence, like a

wave in ocean where is existent of self as a process, and in rolling on makes

self and destroys self.17

Conclusion:

To

conclude, I see the task before us as one of identifying strategies of action

to ensure to understand Buddhism and Science. In this effort, our attention

should first be directed to the doctrinal base and historical experiences with

Buddhism and Science have to bring about the attitudinal change in the minds of

people.

I am grateful to Mr.Capra for his great book

entitled the Tao of physics. There are many interesting points in this

book. I write this essay in following the book. How ever, writings of words

and essay writing system are inter-related facts. Everything exists only the in

fundamental dependence on everything else. That is why if we finally understand

true nature ofourselves, we at the same time understands the true nature of

everything. The great works of Japanese Buddhist scholars including Dogen,

Kukai, Nichren, Shinran, Professor D. T. Suzuki, and Professor Hajime Nakamura indicated

us how the perilous trend can be slowed down, if not reinvent the human

at the species level altogether. Relating to reinvent the human nature

should we suggest the Buddha’s enlightenment process to realize great

compassion lies in humanistic transcendence.

“There is a question of how do we escape from our greed and corporate

greed?”3

Science

without religious morality spells destruction. Science plus religion like

Buddhism without dogma can save the world. The Buddha appears here as the great

teacher of the Middle Path (Buddhism). Mental developments illustrate the

wisdom of the Buddha in insisting on sound ethical basis against an exclusive

on mystic experience.

10

Newsweek, May 7, 2001 , p. 53.

11 Radmila

Moacanin, Jungian Psychology and Buddhism, p. 123

12 Priestley,

C.D.C. The Reality of the Indeterminate Self (Pudgalavada Buddhism),p.

13 Geshe

Kelsang, Gyatso, The Heart Sutra, p.23

16 The Path

Freedom, p. 258

17

Nyanatiloka, Buddhist Dictionary, p. 96

3 Berry , Thomas, The

Great Works, p. 114